Share this

Down memory lane: How Moi was almost toppled in 1982

• Moi was reportedly informed about the impending mutiny but he treated the matter casually.

• Low morale amongst some officers driven by allegations of tribalism within the force was later cited as a motivator behind the failed coup.

Sunday, August 1, 1982, remains one of Kenya’s darkest hours thanks to a group of mutinous Kenya Air Force officers calling themselves People’s Redemption Council.

The lot comprised non-commissioned junior officers led by Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka and Sergeant Pancras Oteyo Okumu.

The group almost rewrote Kenya’s history in the bad books as the second East African nation after Uganda to experience a coup.

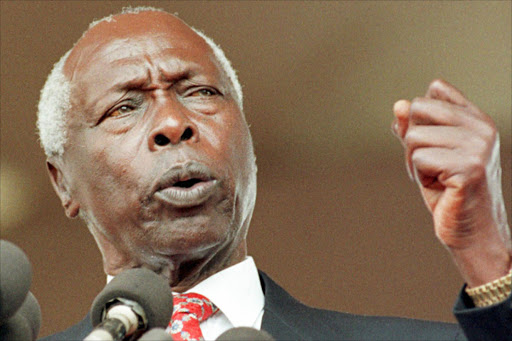

The dissident airmen came very close to overthrowing the late former President Daniel Moi, barely four years after he assumed office following the sudden death of founding President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta in August 1978.

Low morale amongst some officers driven by allegations of tribalism within the force was later cited as a motivator behind the failed coup.

Moi was reportedly informed about the impending mutiny a week prior by then spymaster James Kanyotu and top soldier Gen Jackson Mulinge but he treated the matter casually.

A former army commander later revealed in an interview that the late President didn’t want to create an impression that policemen had been sent to arrest military officers considering the revered Special Branch was a division of the Kenya Police.

Image: FILE

After a series of covert meetings outside the Eastleigh barracks, the coup plotters first engaged in drink partying on the night of July 31, 1982.

At around 3am, they took over Eastleigh Air Base and by 4am, they captured the nearby Embakasi Air Base from where the first bursts of rebel gunfire were heard.

Abduction of Leonard Mambo Mbotela

At 6am, Ochuka and Okumu stormed Voice of Kenya (VOK) broadcasting studios (currently KBC Radio Taifa) on Kijabe Street and forced veteran broadcaster Leonard Mambo Mbotela to announce that the military had overthrown the government.

Mbotela has over the years recounted the events leading up to the moment he announced vivid narrations that paint a grim picture of the horrific turn of events.

He had just dropped his sister at the Kenyatta International Airport and was about to retire to bed at around 4.45am when suddenly gunshots rent the air followed by a vigorous knock on the door a while later.

In his mistaken assumption, the gunshots were police battling thugs and the sudden knock on his door was an emergency call for him to fix something at the studio. He was wrong.

Rebel soldiers had commandeered a VOK driver to his house in Ngara where Ochuka ordered him to hurriedly get dressed.

A shaken company driver, too frightened to speak, beckoned that he was needed outside in a waiting army vehicle whose occupants included coup mastermind Hezekiah Ochuka.

“He shouted at me ‘Leonard Mambo Mbotela, is that you?’ I said yes, it’s me.

“‘I’m giving you three minutes to dress up.’ I asked ‘where are we going?’ He said, ‘don’t ask questions’.”

Mbotela, who was then the head of national and vernacular services, recounted during a previous interview.

“Little did I know that was Ochuka the coup leader,” he said.

Mbotela said he was escorted back to the station at gunpoint in an army Land Rover by a couple of soldiers he said engaged in looting of shops along Moi Avenue.

In the studio, Ochuka hurriedly drafted a script on a piece of paper and ordered him to announce to Kenyans that Moi’s government had been overthrown and that he (Ochuka) was now the president.

“Dear listeners, my name is Leonard Mambo Mbotela from VOK, I have with me here Mr Hezekiah Ochuka who is now the new president of the Republic of Kenya. President Moi’s government has been overthrown. All police are now civilians; all prisoners should be set free. I urge you to stay indoors until further notice,” a shaken Mbotela beamed the message live.

Other than capturing key military installations to advance their agenda, the coup plotters had strategically seized the national broadcaster as an important propaganda tool.

Unlike today where Kenya prides itself on dozens of FM radio stations, VOK was back then the only electronic medium of communication and the rebels were certain their message would reach the entire country.

In the grand scheme of things, one of the coup plotters at the Laikipia Air Base in Nanyuki was leading a plot to bomb State House and the General Service Unit headquarters in Embakasi.

The officer of the rank of a Corporal commandeered three Air Force pilots to fly three armoured fighter jets to Nairobi for the mission with a promise to kill them should they dare to disobey.

The pilots obliged to accomplish the mission but in a scheme of deceit, they communicated via a secret channel and agreed that the captain piloting the fighter jet carrying their captor should execute daring acrobatic manoeuvres and disorient the gun-wielding rebel soldier.

They figured the Corporal holding them at gunpoint had never flown and he wouldn’t withstand the resultant gravitational force following the manoeuvres. The plan worked.

The rebel commander became dizzy and confused. The pilots then dumped the unarmed bombs in Mt Kenya forest and returned to base in Nanyuki where the confused gunman announced to the other airmen that they had bombed Nairobi.

Image: FILE

It so happened that the coup coincided with military war games in Lodwar where most of the top-ranking senior army officers were engaged unaware of what was unfolding in Nairobi, the epicenter of the coup.

In a quick calculation to save the situation, Army Commander Lt Gen Sawe convened a meeting with a couple of his juniors in the dead of the night where he settled on Maj Gen Mohamoud Mohamed, the Deputy Army Commander, to be in charge of operations to suppress the mutiny.

Mohamed quickly assembled a team comprising loyalist officers from the army, special branch and the police to help him accomplish the mission.

Some were dispatched to recapture Eastleigh, Embakasi and Laikipia air bases.

Laikipia and Embakasi were the first to fall as the dissident servicemen were routed by advancing loyalist troops.

Back in the streets of Nairobi, rebel soldiers and university students were all over shouting “Power!” whilst punching in the air with their fists.

Looting was the order of the day as celebrations greeted the air to usher in what the rebels and their supporters, mainly university students, wrongly perceived to be a new dawn.

Businesses were destroyed, people were beaten and women were raped.

Image: FILE

About an hour after Mbotela’s coup announcement, Mohamed and a team of loyal officers from Kahawa Garrison stormed VOK studios.

The goal was to have the rebel airmen surrender peacefully but the plan changed into a full-scale fire exchange prompted by a pre-emptive self-defensive manoeuvre by the advancing party.

The invading soldiers were at most 30 but they inflicted heavy casualties on the rebel troops who were at this point drunk after a night of partying.

“They all fled, including the one who had just declared himself president,” Mbotela, who said he was at this time hiding under a table, said.

The exact number of casualties may never been known but airmen who had laid siege inside the studio were among those killed.

Mohamed ordered Mbotela to go live again, retract his previous announcement, say the coup attempt had been swiftly quelled and President Moi’s government and constitutional order restored.

“I’m General Mohammed. I want you to announce that Nyayo forces have retaken the country,” he said.

Mbotela said Mohamed knew him and this served to reassure him that indeed the ordeal was over.

To assure soldiers across the country that all was now well, Mohamed gave Mbotela a list of names of senior army officers who told him to tell the country they were with him in the studio.

While all this was happening, Kanyotu and his men were hard at work jamming Air Force signals to throw Ochuka and his men into disarray.

Army Commander Sawe also ordered that the communication facility at the Eastleigh Air Base which Ochuka had continued to use to relay threats to him and claim he was the president bombed.

After hours of uncertainty, a devastated Moi who was at the time of the coup at his Kabarak home in Nakuru was driven in an armoured convoy to Nairobi under the watchful eye of his bodyguard Elijah Sumbeiywo.

Once safely installed at State House by the presidential guard late Sunday evening of August 1, 1982, Moi addressed the nation and assured Kenyans that he was back as President.

Outwitted and without his lieutenants most of whom had been felled by loyalist forces, Ochuka fled to Tanzania.

The coup attempt left the Kenya Air Force a tainted entity prompting a series of radical changes.

The force was disbanded and renamed the ‘82 Air Force amid a massive purge in the disciplined forces that ended many careers including that of Ben Gethi, the tough head of the dreaded General Service Unit.

The name ‘82 Air Force was in use for years until a court ruled that it was a non-existent entity in the Constitution and as such, Kenya Air Force was reinstated.

The registration plates of the Airforce vehicles which started with ‘KAF’ before the disbandment were changed to start with ‘AF’.

Eastleigh, Nairobi and Nanyuki air bases were also renamed.

Eastleigh Air Base became Moi Air Base, Nanyuki Air Base became Laikipia Air Base and the Ground Air Defence Unit (GADU) was disbanded.

Airforce uniforms and the Service Flag were also changed and the motto ‘Twatumika Tukiwa Angani’ was dropped in favour of ‘Tuko Imara Angani’.

On August 12, 1982, Maj Gen Mohamoud Mohamed was promoted to the rank of Lt Gen and appointed the KAF Commander.

He would later on in 1986 be appointed Chief of General Staff.

Maj Gen Peter Kariuki, who was the then Commander of the Kenya Air Force was Court Martialed and on January 18, 1983, sentenced to four years behind bars for failing to prevent the coup attempt.

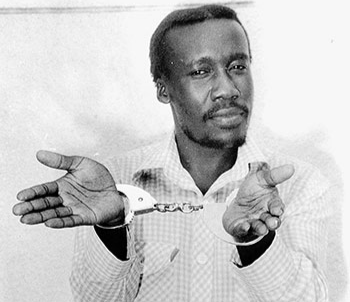

Ochuka, the brains behind the failed coup, was extradited from Tanzania and tried by a court martial.

He was hanged in 1987 alongside his co-conspirator Pancras Oteyo Okumu for treason.

The two remain the last known death row convicts in Kenya whose date with the hangman came to pass.

Although the death penalty is still part of the penal code, all death sentences have over the years been computed to life imprisonment at the judges’ discretion or through a presidential decree.