Health

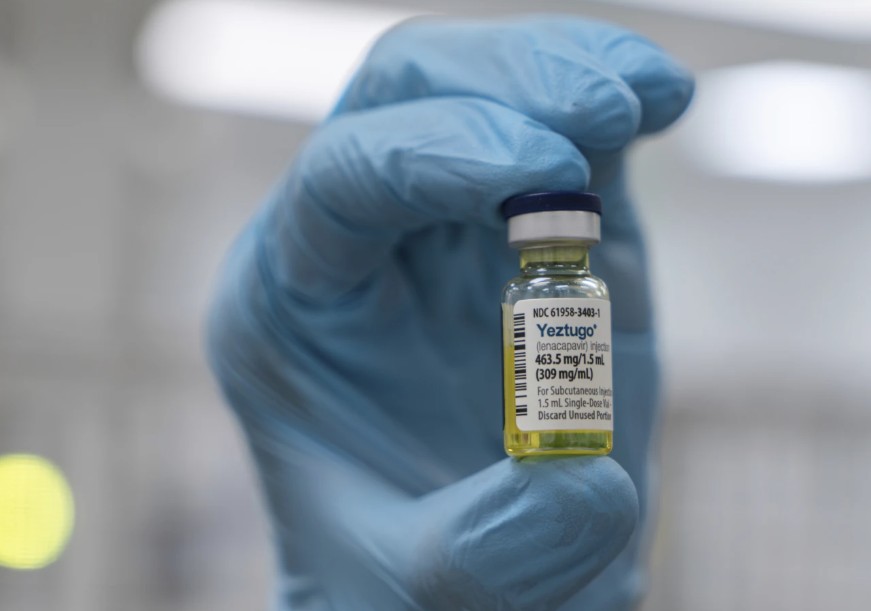

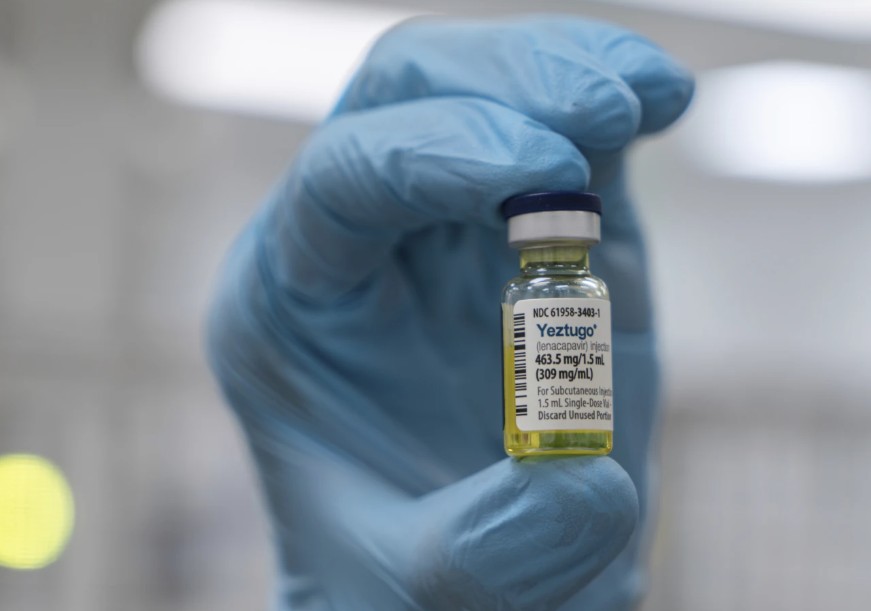

WHO approves injectable lenacapavir in major shift on HIV prevention

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has endorsed i...

Kindly subscribe to Samrack Premium to access this content.

URL Copied

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has endorsed i...

Kindly subscribe to Samrack Premium to access this content.

Get breaking news, community stories, and exclusive insights delivered to your inbox.